Introduction: The Cultural Paradox of Chabuduo

In contemporary China, few concepts generate as much heated debate as chabuduo (差不多), a term that literally translates to “almost the same” or “not much difference.” For Chinese citizens, it represents a pragmatic approach to life’s challenges; for foreign observers, it often symbolizes frustrating quality compromises. This linguistic expression encapsulates a cultural mindset that profoundly shapes everything from manufacturing practices to interpersonal relationships across Chinese society.

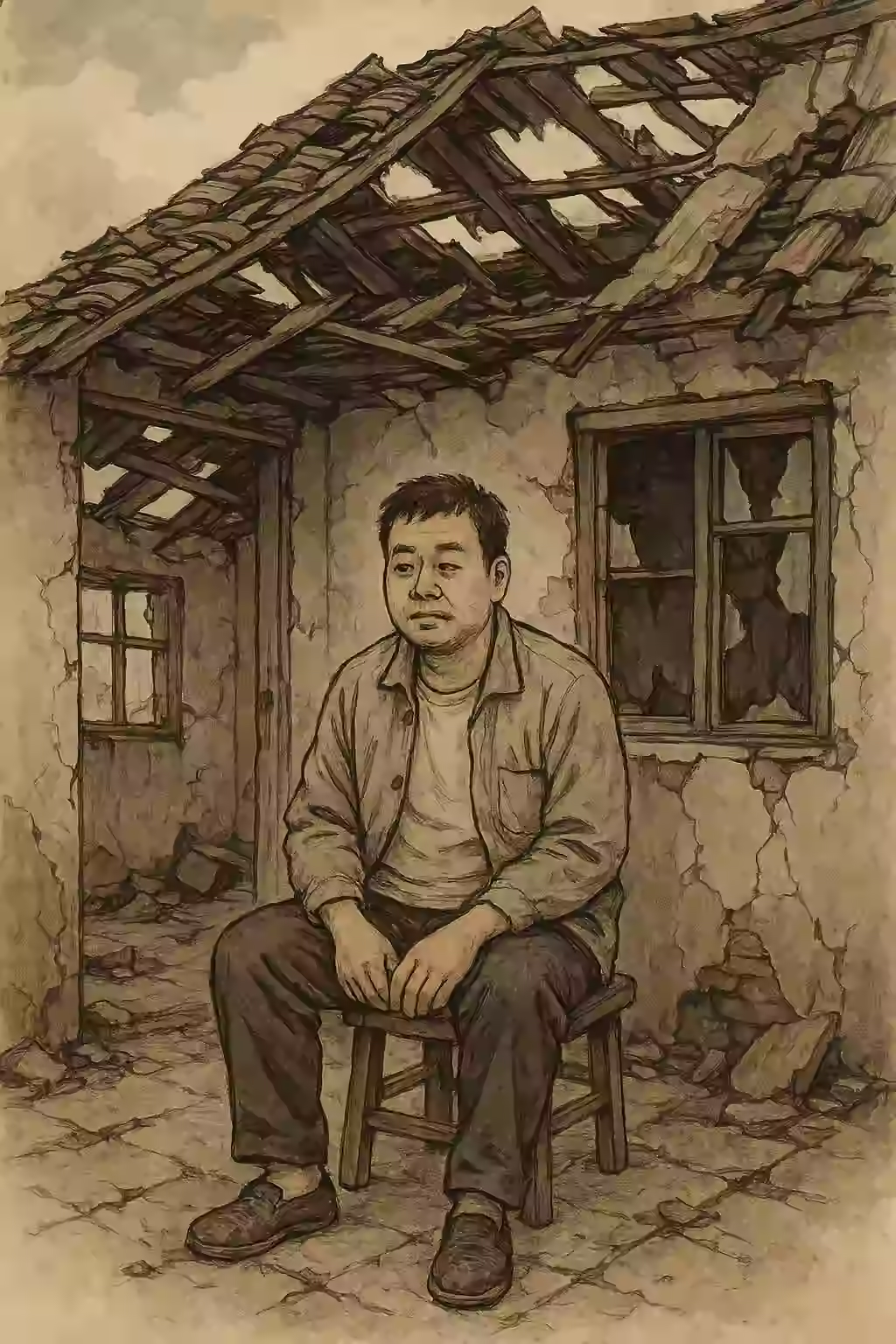

When I first encountered chabuduo during my initial weeks in Beijing, it appeared in the form of a crooked bathroom mirror in my newly renovated apartment. The property manager’s casual dismissal with a shrug and utterance of “chabuduo” revealed something far deeper than mere linguistic expression—it was a window into a complex cultural phenomenon that balances pragmatic acceptance of imperfection with the elaborate social dynamics of preserving dignity (mianzi 面子). These intertwined concepts create a distinctive approach to quality, precision, and problem-solving that continues to influence China’s development trajectory in ways both productive and problematic.

This article examines the historical roots of chabuduo culture, analyzes its manifestations across various sectors of contemporary Chinese society, evaluates its impact on quality and innovation, and explores its future evolution in a rapidly modernizing China. By understanding chabuduo not as a simple cultural quirk but as a complex adaptive response to specific historical and economic circumstances, we gain critical insight into China’s developmental challenges and opportunities in the 21st century.

How do you primarily view the “chabuduo” approach to quality and standards?

- A pragmatic response to real-world constraints

- A frustrating excuse for cutting corners

- An ingenious approach to rapid innovation

- A dangerous attitude in a modern economy

- A cultural trait that’s widely misunderstood

The Historical Foundations of Chabuduo

From Necessity to Cultural Value

The chabuduo mindset did not emerge from cultural laziness or indifference to quality. Rather, it developed as a pragmatic response to millennia of resource scarcity and political tumult where survival often depended on adaptive improvisation[1]. Throughout Chinese history, particularly during periods of famine or political chaos, perfectionism was an unaffordable luxury. When resources were scarce, a functional solution—even if imperfect—was inherently more valuable than an idealized but unattainable one.

This pragmatic approach became particularly vital during China’s tumultuous 20th century. The Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) intensified the chabuduo philosophy as supply chains collapsed and formal economic systems disintegrated. When traditional manufacturing parts became unavailable, farmers and workers had to fashion makeshift replacements. What Westerners might view as “cutting corners” represented, for many Chinese, ingenious adaptation to impossible circumstances[2].

As historian Yohuru Williams notes, the Cultural Revolution represented a severe upheaval that forced practical solutions over idealized ones, creating conditions where immediate functionality necessarily trumped long-term quality concerns[3]. During this period, approximately 20 million urban Chinese youth were relocated to rural areas, disrupting educational systems and professional training while emphasizing revolutionary zeal over technical precision[4].

An elderly factory worker from Shenyang explained this historical reality: “During the 1970s, we had no choice but to be chabuduo. If a machine broke and replacement parts didn’t exist, we made something that worked chabuduo—close enough. Without this thinking, production would have stopped entirely.”

Institutionalization Under Central Planning

The planned economy under Mao Zedong further institutionalized the chabuduo mentality through its emphasis on production quotas rather than quality standards. Factories producing higher quantities of defective goods received more commendation than those producing smaller numbers of higher-quality products. This quantitative prioritization became embedded in industrial practices and social norms throughout the decades of centralized economic planning[5].

The Cultural Revolution particularly damaged China’s educational infrastructure, with schools closed and universities shuttered for years. When educational institutions gradually reopened in the late 1960s and early 1970s, they operated with reduced schooling years and diminished standards—another institutional manifestation of the chabuduo approach to development[6]. While this approach expanded educational access for rural communities, it simultaneously compromised quality and consistency.

These historical circumstances fostered a national psychology where pragmatic compromise became not merely accepted but valorized. The ability to find workable solutions under impossible constraints became regarded as a form of Chinese ingenuity rather than a regrettable compromise—a perspective that continues to influence contemporary attitudes toward quality and precision.

Chabuduo and Face: A Cultural Interaction

Understanding Mianzi and Lian

To comprehend why chabuduo persists in modern China despite its sometimes negative consequences requires examining the concept of “face” (mianzi 面子). Chinese scholar Lu Xun described face as the “guiding principle of the Chinese mind,” underscoring its centrality to Chinese social interactions[7]. Face represents far more than mere embarrassment—it constitutes a sophisticated social currency encompassing honor, reputation, and dignity within China’s collectivist society.

Chinese culture distinguishes between two types of face: lian (臉) and mianzi (面子). Lian represents moral character—the face lost when one behaves dishonorably or fails ethical expectations. Mianzi represents social status and prestige—the face gained through accomplishment and recognition within social hierarchies[8]. This distinction creates nuanced social dynamics that influence how problems are addressed and resolved.

Face can be lost (diulian 丢脸) through various social mechanisms:

- Public criticism or correction

- Having mistakes exposed before peers

- Being unable to answer questions or demonstrate competence

- Having authority challenged

- Being forced to admit ignorance or error

The interaction between chabuduo and face creates a self-reinforcing cycle. When quality problems arise, directly acknowledging them risks causing face loss for those responsible. The chabuduo justification provides a culturally acceptable way to acknowledge imperfection without assigning blame or causing face loss. This preserves social harmony but often at the expense of addressing underlying quality issues[9].

The Vicious Cycle of Quality Avoidance

The intertwining of chabuduo and face concerns creates a distinctive approach to quality management in Chinese contexts. Consider what happens in a typical quality dispute between a foreign buyer and Chinese manufacturer:

A European textile importer receives fabrics with visible color variations. When confronted, the factory owner insists they’re “chabuduo”—close enough. The real problem isn’t perceptual (the manufacturer can clearly see the difference) but social (admitting the mistake would cause face loss). Rather than acknowledging the problem, he doubles down on asserting that the difference is acceptable within cultural standards.

This dynamic—where chabuduo serves as both cause and justification for quality issues—creates a vicious cycle:

- Mistakes happen initially due to the chabuduo attitude toward precision

- Nobody directly addresses these mistakes to avoid causing face loss

- Problems remain uncorrected under the chabuduo justification

- The pattern reinforces itself, creating a culture where quality improvements become difficult to implement

As the Chinese saying goes, “Saving face is more important than saving lives” (Baohu mianzi bi baohu shengming geng zhongyao 保护面子比保护生命更重要), highlighting how powerfully face concerns can override other considerations, including quality and safety.

The Double-Edged Sword: Benefits and Costs of Chabuduo

The Human Cost of “Close Enough”

The darker consequences of chabuduo thinking emerge most clearly in safety-critical contexts. The Sichuan earthquake of 2008 provided a tragic illustration when poorly constructed schools collapsed while nearby government buildings remained standing. Investigations revealed that construction companies had used inadequate materials and skipped reinforcement steps—chabuduo construction that resulted in thousands of children’s deaths[10].

Similarly, the 2015 chemical explosion in Tianjin that killed 173 people stemmed from hazardous chemicals stored with chabuduo attention to safety regulations. Warehouse operators had taken shortcuts on fire prevention systems, assuming nothing would go wrong—a devastating miscalculation[11].

Food safety scandals repeatedly demonstrate the dangers of chabuduo. The 2008 melamine milk scandal, where manufacturers added industrial chemicals to boost protein readings—a chabuduo approach to meeting nutritional requirements—caused kidney failure in hundreds of thousands of infants[12].

These tragedies represent the most extreme consequences of chabuduo thinking, but daily life is filled with smaller manifestations: escalators that malfunction because of chabuduo maintenance, medications with chabuduo adherence to formulations, and buildings with chabuduo attention to electrical safety. When applied to contexts where precision matters, the cultural acceptance of “close enough” can create significant harms.

The Counterintuitive Innovation Engine

Paradoxically, while chabuduo creates dangerous situations in precision-dependent contexts, it simultaneously fuels innovation in others. China’s technology sector demonstrates this contradiction perfectly.

In Shenzhen’s electronics markets, the chabuduo approach to intellectual property and design specifications created “shanzhai” (山寨) culture—a freewheeling innovation ecosystem where products are rapidly iterated and improved through loose adherence to formal standards[13]. Shanzhai represents not mere copying but adaptive innovation through rapid cycles of imitation, enhancement, and localization.

David Li, who runs a hardware innovation hub in Shenzhen, explains this dynamic: “Western innovation is often slowed by perfectionism—engineers won’t release until every feature is polished. Here, the chabuduo attitude means companies release products that are ‘good enough,’ get market feedback, and iterate rapidly. It creates faster innovation cycles, even if individual products aren’t perfect.”

This chabuduo-driven innovation has produced remarkable successes. Chinese smartphone manufacturers like Xiaomi initially created “chabuduo iPhones”—devices that borrowed from Apple’s design language but added locally relevant features at lower price points. Over time, these companies evolved from chabuduo imitators to genuine innovators now setting global smartphone trends[14].

The shanzhai ecosystem demonstrates how the chabuduo mindset, when combined with open sharing and rapid iteration, can become a powerful innovation model. The same cultural trait that produces quality compromises in some contexts enables adaptability and market responsiveness in others[15].

Strategic Chabuduo: Manipulation of Cultural Understanding

While chabuduo often reflects genuine cultural differences, some businesses deliberately exploit Westerners’ misunderstanding of these concepts. This “strategic chabuduo” appears in what quality control experts call “quality fade”—where manufacturers deliver excellent initial samples but gradually reduce quality in subsequent production runs[16].

An American furniture importer described this pattern: “Our first shipment was perfect—exactly to specifications. The second had minor issues we overlooked. By the fifth shipment, the wood quality had degraded significantly, hardware was cheaper, and finishes were thinner. When confronted, the factory owner simply said it was ‘chabuduo’ the same quality—but this wasn’t cultural misunderstanding, it was calculated profit-seeking.”

This strategic exploitation becomes particularly effective when combined with face dynamics. Foreign companies hesitate to directly confront suppliers about quality issues for fear of disrupting relationships—exactly what calculating suppliers count on.

Zhou Min, who previously managed exports at a factory in Yiwu, candidly admitted: “When foreign buyers don’t understand face dynamics, we sometimes take advantage. If we can save 15% using different materials but the product looks ‘chabuduo’ the same, many foreign companies won’t push too hard because they worry about damaging relationships. They think refusing ‘chabuduo’ quality will make us lose face.”

This strategic manipulation illuminates the complexity of cross-cultural business interactions. What appears as cultural misunderstanding may sometimes be deliberate exploitation of cultural differences. Understanding chabuduo not just as a cultural trait but as a potential business strategy allows foreign partners to navigate these dynamics more effectively.

Which factor do you believe most strongly reinforces “chabuduo” culture in modern China?

- The importance of “face” (mianzi) in social interactions

- Historical resource scarcity and economic constraints

- Rapid economic development pressures

- Weak regulatory enforcement

- Deliberate business strategy for profit maximization

The Chabuduo Defense: When Reality Becomes Negotiable

The most perplexing manifestation of the chabuduo-face relationship occurs when obvious quality defects are defended despite clear evidence. This “chabuduo defense” reveals how powerfully face preservation can override objective reality[17].

A European electronics importer described this phenomenon: “We received a shipment where 40% of units had visible scratches on the screens. When we showed photos to our supplier, they insisted the scratches were ‘chabuduo invisible’ and wouldn’t affect functionality. The fascinating part wasn’t just their denial but their genuine indignation when we insisted on replacements—as if we were being unreasonably picky.”

This defense mechanism stems from the devastating face loss that acknowledging mistakes would entail. In Chinese business culture, acknowledging quality failure implies incompetence or dishonesty—catastrophic to one’s social standing. The chabuduo defense serves as a psychological shield against this threat[18].

For foreigners, this defense mechanism can seem delusional or dishonest. But understanding it as a face-preservation strategy provides crucial context. The supplier isn’t necessarily denying reality but protecting their social standing through culturally sanctioned means.

Government Response: Fighting Chabuduo from Above

The Chinese government isn’t blind to problems created by chabuduo culture. While rarely acknowledging the term directly, authorities have launched numerous campaigns targeting quality and safety issues stemming from chabuduo thinking.

Following the 2008 melamine milk scandal, Beijing implemented sweeping food safety reforms and severely punished responsible executives—some received death sentences—sending a clear message that chabuduo standards in food production would no longer be tolerated[19].

In 2015, Premier Li Keqiang explicitly denounced shoddy workmanship in infrastructure projects, stating, “If a project is of poor quality, those responsible should be held accountable for life.” While he didn’t use the term chabuduo, the target was clear—the attitude that “close enough” was acceptable in critical infrastructure[20].

Despite these efforts, changing deeply embedded cultural attitudes presents significant challenges. Regulations are often inconsistently enforced, creating opportunities for chabuduo compliance—following rules just enough to avoid penalties but not enough to achieve their intended purpose.

The Generational Divide: Changing Attitudes

Attitudes toward chabuduo vary significantly across generations, reflecting China’s rapid development. Younger, globally-educated Chinese professionals often reject the chabuduo mindset that their parents accepted as normal.

Liu Ming, a 29-year-old engineer who studied in Germany before returning to Shanghai, explained this shift: “My grandparents think chabuduo is sensible frugality—why waste resources pursuing needless perfection? My parents accept it as the way things work in China. But my generation sees it as embarrassing. We know China can do better.”

This generational divide appears most starkly in technology sectors. China’s most globally successful companies have explicitly built corporate cultures that reject chabuduo thinking. Huawei’s founder Ren Zhengfei famously established a zero-tolerance policy for quality defects. Alibaba and Tencent similarly enforce global quality standards rather than accepting chabuduo performance[21].

The evolution of attitudes toward chabuduo reflects broader changes in Chinese society as it moves from developing to developed status. As China shifts from manufacturing low-value goods to competing on innovation, quality, and brand reputation, the cultural acceptability of “close enough” is increasingly questioned.

The Chabuduo-Shanzhai Innovation Spectrum

The relationship between chabuduo and China’s emerging innovation capabilities deserves deeper exploration. The shanzhai phenomenon—initially dismissed as mere counterfeiting—has evolved into a distinctive innovation model that shares certain characteristics with chabuduo culture while transcending its limitations[22].

Shanzhai manufacturing began as knockoffs of popular brands but has evolved toward what scholars call “innovative imitation” and eventually “novel imitation.” Companies like Xiaomi, once criticized as iPhone copycats, have become global innovation leaders through this evolutionary process[23]. Their success demonstrates how the chabuduo attitude toward intellectual property can, under certain conditions, foster genuine innovation through adaptation and localization.

The key distinction lies in purpose and outcome. When chabuduo justifies cutting corners to reduce costs or effort, it typically undermines quality. But when applied to rapid prototyping and iteration, it can accelerate innovation cycles by emphasizing functionality over perfection and market fit over originality.

Silvia Lindtner, a research scientist studying Chinese innovation, notes: “China’s ‘open manufacturing’ has developed in small-scale factories over the last 20 years…As China’s DIY makers are coming together with manufacturers, they are spurring a shift in industrial production, from ‘made in China’ to ‘made with China’”[24].

This innovation approach relies on several mechanisms:

- Rapid iteration: Products are released quickly to gain market feedback rather than perfected internally

- Open sharing: Design improvements are freely shared among manufacturers rather than protected

- Localization: Products are adapted to specific market needs rather than standardized

- Low-cost experimentation: The tolerance for imperfection enables more experimentation with fewer resources

This model challenges Western assumptions about innovation requiring strong IP protection and original invention. Instead, it suggests that under certain conditions, a more fluid approach to intellectual property combined with rapid iteration can create a different but equally valuable innovation pathway.

When Cultures Collide: International Implications

As China deepens its global engagement, the clash between chabuduo attitudes and international standards creates fascinating cultural confrontations. These tensions reveal fundamentally different ways of thinking about standards, relationships, and accountability across cultures.

For multinational corporations operating in China, navigating chabuduo culture while maintaining global quality standards becomes a delicate balancing act. Those who succeed find ways to respect face while still enforcing precision—often by creating hybrid systems that bridge Chinese and Western approaches[25].

Sarah Johnson, an American quality director for a manufacturing operation in Suzhou, described her evolution: “When I first arrived, I’d directly point out quality issues, causing tremendous face loss and resentment. I eventually developed a different approach—praising the team’s progress while gently introducing ‘even higher standards’ as a collaborative goal. We maintained global quality requirements but wrapped them in face-preserving language.”

Chinese companies expanding internationally face the opposite challenge—adapting from chabuduo flexibility to the precision expectations of global markets. The most successful recognize that what works domestically may damage their brand abroad and develop different quality systems for different markets.

This cultural collision creates learning opportunities in both directions. Western businesses can learn from China’s adaptability and pragmatism, while Chinese firms benefit from adopting global quality standards. The companies that thrive are those that recognize culture as neither static nor deterministic but as a set of adaptive responses that can evolve with changing circumstances.

The Future Trajectory: Evolution, Not Extinction

The evidence suggests chabuduo isn’t disappearing but evolving—certain aspects fading while others transform or persist in specific contexts.

Economic incentives drive much of this evolution. As Chinese companies climb the value chain, the costs of chabuduo quality increase while the benefits decrease. Factories making simple products can survive with chabuduo standards; companies developing advanced semiconductors or aerospace components cannot[26].

Government policies also push against traditional chabuduo attitudes, particularly in strategic industries where quality directly impacts national goals. China’s ambitions in aerospace, semiconductors, AI, and green technology all require transcending chabuduo limitations.

However, some aspects of chabuduo culture appear remarkably persistent, particularly in sectors without strong international competition or where face dynamics remain powerful. Construction, local services, and government bureaucracy often maintain chabuduo practices despite modernization in other areas.

Perhaps most interestingly, certain aspects of chabuduo culture are being consciously preserved as strategic assets while others are discarded. The rapid iteration and pragmatic adaptation that chabuduo enables in innovation contexts are increasingly valued, even as the quality compromises it produces in manufacturing are rejected.

As one Chinese tech entrepreneur put it: “We’re learning to keep the good parts of chabuduo—the adaptability, speed, and pragmatism—while eliminating the bad parts like quality inconsistency and safety compromises. It’s not about abandoning our culture but refining it for a new era.”

Beyond Stereotypes: Chabuduo in Global Context

While this analysis has focused on chabuduo as a distinctively Chinese phenomenon, it’s important to recognize that all cultures contain similar adaptive responses to resource constraints and social pressures. The American “good enough for government work” or the Italian concept of “arrangiarsi” (making do with what’s available) reflect similar pragmatic compromises in different cultural contexts.

What makes chabuduo distinctive isn’t its existence but its particular manifestation within Chinese social dynamics—especially its interaction with face concerns and its institutionalization during China’s rapid industrialization. These factors created a more pervasive and commercially significant version of a universal human tendency toward pragmatic compromise.

Understanding chabuduo in this broader context helps avoid cultural essentialism or stereotyping. The phenomenon isn’t an inherent Chinese characteristic but a cultural adaptation that emerged from specific historical and economic circumstances—and one that continues to evolve as those circumstances change.

The Adaptive Evolution of Chabuduo

For foreigners engaging with China, understanding the chabuduo-face dynamic provides crucial insight into behaviors that might otherwise seem incomprehensible or frustrating.

The skilled foreign manager in China learns to spot the difference between genuine cultural chabuduo and its strategic exploitation. They develop communication approaches that address quality issues while preserving face, creating pathways for quality improvement without triggering defensive reactions[27].

They recognize that what constitutes “good enough” isn’t an objective measure but a value judgment shaped by history, economics, and social structures. As these different systems interact in a globalized economy, they create friction points that go far beyond technical specifications to fundamental questions of how different societies define excellence.

And perhaps most importantly, they understand that cultural patterns like chabuduo aren’t fixed traits but adaptive responses to specific historical and economic circumstances. As China continues its remarkable development journey, these patterns themselves will transform, sometimes gradually and sometimes dramatically, but always reflecting the evolving needs and aspirations of the society they serve.

In the future, chabuduo may become less a philosophy of compromise and more a philosophy of pragmatic innovation—preserving the adaptability while discarding the quality concessions. This evolution would represent not the abandonment of a cultural tradition but its refinement and adaptation to new circumstances—a process entirely consistent with the pragmatic spirit of chabuduo itself.

In your experience, how is “chabuduo” culture evolving in China’s global industries?

- Rapidly disappearing as China climbs the value chain

- Transforming into a unique innovation advantage

- Persisting in some sectors while fading in others

- Being strategically deployed depending on market

- Becoming more entrenched due to nationalist pride

The China Expat Society, “The Chabuduo Mindset,” 2020. ↩︎

Aeon, “What Chinese Corner Cutting Reveals About Modernity,” 2016. ↩︎

Williams, Yohuru, “What Was the Cultural Revolution?,” HISTORY, 2025. ↩︎

Stanford University, “Introduction to the Cultural Revolution,” SPICE FSI, 2014. ↩︎

Britannica, “China - Consequences of the Cultural Revolution,” 1998. ↩︎

Wikipedia, “Cultural Revolution,” 2025. ↩︎

The Greater China Journal, “The Concept of Face in Chinese Culture and the Difference Between Mianzi and Lian,” 2024. ↩︎

Commisceo Global, “Mianzi – The Concept of Face in Chinese Culture,” 2023. ↩︎

China-Mike, “The Cult of Face in China,” 2024. ↩︎

BBC News, “China quake: How ‘tofu schools’ collapsed,” 2009. ↩︎

The Guardian, “Tianjin explosion: China sets final death toll at 173, ending search for survivors,” 2015. ↩︎

The South China Morning Post, “Li Keqiang vows accountability for poor-quality infrastructure,” 2015. ↩︎

CCCB LAB, “The Maker Culture in China (II): Shanzhai, Emerging Innovation in an Open Manufacturing Ecosystem,” 2016. ↩︎

Thunderbird International Business Review, “A global perspective on combating Shanzhai products,” 2023. ↩︎

ResearchGate, “Renegades on the Frontier of Innovation: The Shanzhai Grassroots Communities of Shenzhen in China’s Creative Economy,” 2012. ↩︎

Midler, Paul, “Poorly Made in China: An Insider’s Account of the China Production Game,” 2009. ↩︎

Sourcing Allies, “‘Cha Bu Duo’: The expression that fills western manufacturers in China with dread,” 2023. ↩︎

The Global Sourcing Blog, “The Chinese ‘Chabuduo’ Attitude,” 2014. ↩︎

The South China Morning Post, “China’s youth reject chabuduo mentality,” 2023. ↩︎

The South China Morning Post, “Li Keqiang vows accountability for poor-quality infrastructure,” 2015. ↩︎

Financial Times, “Jack Ma’s management philosophy and Alibaba corporate culture,” 2018. ↩︎

Launch Factory 88, “Innovation in China: The Art of Shanzhai,” 2015. ↩︎

Emerald Insight, “Innovation-orientation, dynamic capabilities and evolution of the informal Shanzhai firms in China: A case study,” 2016. ↩︎

Launch Factory 88, “Innovation in China: The Art of Shanzhai,” 2015. ↩︎

The Economist, “Cultural conflicts in multinational joint ventures,” 2022. ↩︎

Harris-Sliwoski LLP, “The Perils of China’s ‘Good Enough’ Attitude on Manufacturing,” 2023. ↩︎

Foreign Policy, “When Western Quality Standards Meet Chinese Pragmatism,” 2021. ↩︎