The “Qigong Fever” of 1980s-1990s China represents one of the most extraordinary mass social phenomena in modern Chinese history. At its peak, this movement involved 60-200 million practitioners across over 2,000 organizations[1], making it one of the largest spiritual movements of the 20th century. The scandal that ultimately brought it down, epitomized by Zhang Xiangyu’s 1990 case, marked a decisive turning point in China’s approach to traditional practices, scientific authority, and social control.

Zhang Xiangyu’s spectacular rise and fall

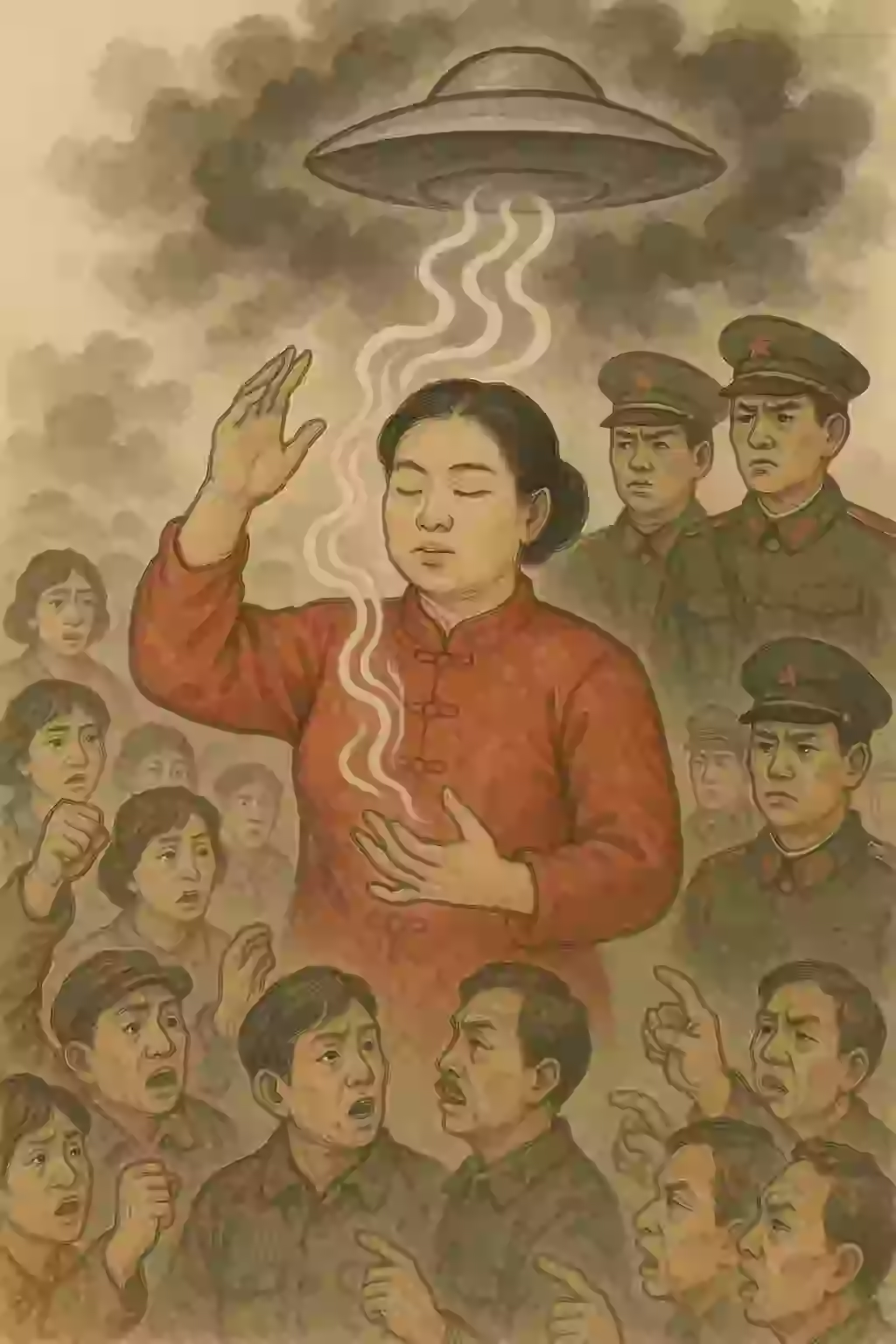

Zhang Xiangyu (张香玉) became the most notorious figure of the Qigong Fever when her activities in 1990 triggered a government crackdown that would reshape China’s spiritual landscape. A former factory worker turned qigong “master,” Zhang claimed supernatural abilities including communication with extraterrestrial beings and universal healing powers[2]. Her story exemplifies how charismatic authority, mass psychology, and institutional failure combined to create a dangerous cultural phenomenon.

Zhang’s background was remarkably ordinary. After graduating junior high school, she worked in a Beijing factory for five years before retirement in 1963. She then spent decades as an actor in regional drama troupes across Shanxi, Hebei, and finally Qinghai provinces[3]. Her transformation began in 1986 when she claimed to have gained “special functions” (特异功能) through mystical communication with nature. By 1987, she had attracted the attention of the China Qigong Science Research Association, which appointed her as a “Special Member” and authorized her to establish the “Natural Center Qigong Research Institute” in 1989[4].

The Beijing events of March 1990 revealed the movement’s explosive potential. Zhang conducted 27 sessions between March 18-31, teaching 11,693 people and generating 409,255 yuan in revenue[5]. Her sessions, held in Haidian District’s Beitaipingzhuang Agricultural Market, attracted 500 people per session at 35 yuan each. The scale was unprecedented: millions of “pilgrims” from multiple provinces converged on Beijing, causing severe traffic congestion as people sought to witness her perform in “cosmic language” (宇宙语)[6].

Zhang’s methods combined theatrical performance with spiritual authority. Her sessions involved incomprehensible vocalizations described as mixing various languages and opera styles, with participants arranged in formations responding with trance-like emotional states. The government response was swift and decisive. After initial warnings on March 21, Zhang was detained on April 14, 1990, formally arrested on December 5, and her association membership revoked on December 11[7]. Her conviction in 1993 marked the end of an era, as multiple patients had become ill under her treatment and some died[8].

The broader phenomenon that captivated a nation

The Qigong Fever emerged from the unique conditions of post-Cultural Revolution China, representing what scholars call “collective effervescence” in a society searching for meaning and identity[9]. The movement’s evolution can be traced through distinct phases that reveal its complex relationship with Chinese state power and popular spirituality.

The initial rise (1978-1985) began with Tang Yu, a Dazu schoolboy who gained national attention for allegedly reading Chinese characters with his ears. The 1979 official legitimation of qigong marked the beginning of extraordinary state support[10], with Gu Hansen of Shanghai Institute of Atomic Research reporting the first external measurements of qi. The establishment of the China Qigong Science Research Society in 1985 provided institutional framework for what became a mass movement[11].

The peak period (1990-1995) saw the phenomenon reach extraordinary proportions. Mass qi-emission lectures filled sports stadiums, with millions practicing qigong daily in urban parks[12]. The movement’s commercialization accelerated rapidly, with major organizations generating billions in revenue through hierarchical training systems. Zhang Hongbao’s Zhong Gong claimed 20-38 million followers at its peak[13], while Li Hongzhi’s Falun Gong, introduced in 1992, would become the most famous qigong practice globally[14].

The systematic crackdown (1995-1999) reflected growing government concern about independent social organization. The April 25, 1999 demonstration by 10,000 Falun Gong practitioners at Zhongnanhai triggered the final phase of suppression[15]. By December 1999, major qigong organizations were banned, their assets confiscated, and hundreds of key members arrested. The era of mass qigong movements had ended[16].

Masters, scandals, and the culture of charismatic authority

The Qigong Fever produced a pantheon of charismatic masters whose careers illuminate the movement’s evolution from spiritual practice to commercial enterprise to perceived political threat. These figures demonstrate how traditional Chinese concepts of spiritual authority adapted to modern mass media and state institutions.

Zhang Baosheng (1960-2018), called “superman,” “Chinese God,” and “living buddha,” represented the pinnacle of state-sanctioned paranormal research[17]. Transferred to the military’s 507 Institute in 1983, he lived in luxury with government protection while claiming abilities including x-ray vision, telekinesis, and healing powers. His exposure by the Committee for Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal in 1988 foreshadowed the movement’s eventual scientific discrediting[18].

Yan Xin (b. 1950) pioneered the mass spectacle aspect of qigong culture through “power-displaying reports” that drew thousands to sports stadiums. His claims of remote healing and molecular structure changes were later retracted from scientific journals due to lack of reproducible methods[19]. His 1990 flight to the United States, where he obtained permanent residency, reflected the internationalization of qigong culture.

Zhang Hongbao’s Zhong Gong demonstrated the movement’s commercial potential. Founded in 1987, it developed an 8-level training system based on engineering principles and built a massive commercial empire employing 100,000 people[20]. Zhang’s 2000 flight to the US after rape charges and his 2006 death in a car accident marked the end of one of China’s largest spiritual-commercial enterprises[21].

Government responses and the politics of regulation

The Chinese government’s relationship with qigong evolved from enthusiastic support to systematic suppression, reflecting broader tensions between traditional culture, scientific authority, and political control in post-Mao China. This evolution reveals how the party-state attempted to harness popular spiritual movements for legitimacy while maintaining ultimate control over social organization.

Initial government support (1980s-early 1990s) was remarkable in its breadth and institutional commitment. Qigong was officially recognized as “precious scientific heritage” and integrated into the standard medical curriculum[22]. The establishment of the China Qigong Science Research Society in 1985, followed by Document No. 128 in 1987 promoting ESP research in educational institutions, demonstrated unprecedented state endorsement of paranormal investigation[23].

High-level political support came from influential figures including Qian Xuesen, China’s leading rocket scientist, who advocated for “somatic science” (人体科学) as a new field of research[24]. Former general Zhang Zhenhuan founded and directed the China Qigong Science Research Society, while sports administrator Wu Shaozu controlled research funding. This elite support legitimized qigong as a uniquely Chinese contribution to scientific revolution[25].

The transition to suspicion and control began in 1994 with “Several Opinions on Strengthening the Popularization of Science,” promoting fact-based findings over paranormal claims. The 1995 mandate requiring all qigong groups to establish Communist Party branches marked the beginning of systematic political control[26]. By 1996, state media began publishing critical articles, and the labeling of 15 groups as “evil cults” signaled the end of government tolerance[27].

The final crackdown (1999) was triggered by the Falun Gong demonstration at Zhongnanhai, which the government interpreted as a direct challenge to its authority. The systematic banning of independent qigong organizations, asset confiscation, and mass arrests marked the end of the movement as a significant social force[28]. Post-1999 regulation restricts qigong practice to government-approved forms under strict institutional control[29].

Academic analysis of a cultural phenomenon

Scholarly analysis of the Qigong Fever reveals a complex phenomenon that cannot be reduced to simple explanations of fraud or superstition. Leading academics have identified multiple intersecting factors that created the conditions for this extraordinary social movement, offering insights into post-revolutionary Chinese society and the dynamics of modernization.

David Palmer’s “Qigong Fever: Body, Science, and Utopia in China” (2007) provides the definitive analysis[30], winning the 2008 Francis L.K. Hsu Book Prize and establishing the framework for understanding qigong as a form of “collective effervescence” in post-totalitarian China. Palmer’s work demonstrates how the movement emerged from the intersection of cultural trauma, identity crisis, and the search for a uniquely Chinese path to modernity.

The post-Cultural Revolution context was crucial. The systematic destruction of traditional culture during 1966-1976 created an ideological vacuum that qigong helped fill[31]. Palmer identifies this as a period of “somatization of suffering,” where Chinese people rediscovered their bodies and subjective capacities after years of controlled collective existence. The movement offered what Palmer calls “the promise of an all-powerful technology of the body rooted in the mysteries of Chinese culture”[32].

Nancy Chen’s “Breathing Spaces: Qigong, Psychiatry, and Healing in China” (2003) provides crucial medical anthropological perspective, analyzing qigong’s role during China’s transition from state-subsidized to market-based healthcare. Chen’s work reveals how qigong served critical social organizational functions through informal networks[33], helping people navigate the collapse of traditional social support systems.

The attempt to reconcile traditional practices with scientific materialism represents one of the phenomenon’s most distinctive features. Qian Xuesen’s advocacy for “somatic science” reflected genuine elite belief that qi could be measured as electromagnetic radiation and explained through scientific principles[34]. This integration of traditional cosmology with modern scientific discourse created a unique cultural synthesis that legitimized spiritual practices within a materialist ideological framework.

Traditional practices meet modern science and superstition

The Qigong Fever represents a fascinating case study in how traditional Chinese practices adapted to modern scientific discourse, creating what scholars call a “qigong science” paradigm that attempted to reconcile ancient wisdom with contemporary research methods. This intersection reveals both the possibilities and pitfalls of cultural modernization in a revolutionary society.

The scientific legitimation of qigong began in 1979 with claims that qi could be measured as electromagnetic radiation and produce external effects[35]. Research at prestigious institutions including Tsinghua University and the Chinese Academy of Sciences reported findings that seemed to validate traditional claims about life energy and spiritual power. This scientific endorsement was crucial to the movement’s expansion, providing intellectual cover for practices that might otherwise be dismissed as superstition.

The “somatic science” theory developed by Qian Xuesen represented the most sophisticated attempt to create a scientific framework for qigong practices. This approach claimed that traditional Chinese concepts of qi, meridians, and energy cultivation could be understood through modern physics and biology[36]. The integration of ESP research, psychokinesis studies, and electromagnetic field measurements created an impressive intellectual edifice that attracted serious scientific attention.

However, the scientific claims gradually unraveled under scrutiny. The 1988 exposure of Zhang Baosheng’s fraud by international investigators marked the beginning of systematic debunking[37]. Claims of remote healing, molecular structure changes, and paranormal abilities were retracted from scientific journals due to lack of reproducible methods[38]. The collapse of scientific credibility undermined the movement’s intellectual foundation and contributed to its political suppression.

The traditional elements that survived this scientific integration reveal qigong’s authentic cultural roots. Traditional Daoist and Buddhist cosmologies were successfully incorporated through what Palmer calls “extra-institutional channels”[39], allowing genuine spiritual practices to continue alongside fraudulent claims. The persistence of master-disciple transmission networks, meditation techniques, and therapeutic exercises demonstrates the movement’s connection to authentic Chinese cultural traditions.

Contemporary parallels and ongoing exposures

The fundamental dynamics that created the Qigong Fever continue to manifest in contemporary China, albeit in modified forms that reflect changed social conditions and regulatory environments. Modern cases of fraudulent martial arts masters and spiritual charlatans demonstrate the persistence of charismatic authority and popular credulity[40], while new forms of debunking and exposure reveal evolving approaches to cultural authenticity and scientific validation.

The Wang Lin case (2013-2017) exemplified the continuation of fraudulent spiritual practices in modern China. Wang attracted celebrity followers including Jackie Chan, Jet Li, and Jack Ma through claims of supernatural abilities[41], ultimately facing charges of murder, kidnapping, fraud, and illegal firearms possession. His connections to high-ranking officials highlighted ongoing concerns about corruption and the exploitation of traditional beliefs for personal gain[42].

Xu Xiaodong’s systematic exposure of fake martial arts masters represents a new form of cultural authentication[43], using modern media to challenge fraudulent claims through direct physical confrontation. His viral defeats of self-proclaimed masters sparked national debates about the relationship between traditional practices and contemporary reality. However, his legal troubles and forced use of humiliating stage names demonstrate the political sensitivities surrounding cultural criticism in contemporary China[44].

The Shaolin Monastery commercialization scandal revealed how even authentic traditional institutions can be corrupted by commercial pressures. Allegations against Abbott Shi Yongxin included financial impropriety, sexual misconduct, and the transformation of sacred sites into profit-driven enterprises[45]. This case illustrates the ongoing tension between cultural preservation and economic development in modern China.

Social media and digital platforms have fundamentally changed the dynamics of exposure and verification. Modern debunking efforts can reach millions instantly, creating new forms of accountability for fraudulent practitioners[46]. However, the same platforms also enable the rapid spread of misinformation and the creation of new forms of spiritual authority that may be even more difficult to regulate than traditional master-disciple relationships.

Scholarly perspectives on tradition and authenticity

Academic approaches to the Qigong Fever demonstrate the complexity of evaluating cultural phenomena that intersect tradition, science, and social organization. Leading scholars have developed nuanced frameworks that acknowledge both the fraudulent aspects of the movement and the authentic cultural traditions it represented[47], offering models for understanding similar phenomena without dismissing traditional practices entirely.

Palmer’s analytical framework distinguishes between different “waves of replication” that intersected during the Qigong Fever: traditional body technologies, religious cosmologies, scientific rationalism, state regulatory apparatus, and mass media technologies. This approach allows for recognition that authentic traditional practices coexisted with fraudulent claims and political manipulation[48]. The movement’s complexity cannot be reduced to simple categories of truth or falsehood.

Chen’s medical anthropological perspective emphasizes the genuine social functions served by qigong practice, particularly during China’s healthcare transition. Her work documents legitimate therapeutic benefits while acknowledging the dangers of unsupervised practice and fraudulent claims[49]. This balanced approach recognizes that traditional practices can serve important social and medical functions even when embedded in problematic institutional contexts.

Contemporary scholarly consensus emphasizes the need for evidence-based evaluation of traditional practices without cultural dismissal. Modern research supports qigong’s efficacy for specific conditions including balance improvement, chronic pain management, anxiety reduction, and cardiorespiratory health[50]. This scientific validation provides a foundation for preserving authentic practices while rejecting fraudulent claims.

The development of quality standards and proper training protocols represents an important evolution in the field. The establishment of the Chinese Health Qigong Association in 2000 and the restriction of public practice to government-approved forms has created a regulatory framework that protects consumers while preserving traditional knowledge[51]. This approach offers a model for other countries seeking to integrate traditional practices into modern healthcare systems.

Documented harm and the human cost

The human cost of the Qigong Fever reveals the dangers of unregulated spiritual movements and the exploitation of vulnerable populations seeking health and meaning. Documentation of specific harms includes medical exploitation, psychological damage, financial fraud, and in some cases, preventable deaths[52]. These cases provide crucial evidence for understanding why government intervention became necessary and how similar phenomena might be prevented in the future.

Medical exploitation represented one of the most serious categories of harm. Unqualified practitioners claiming to cure serious illnesses like cancer led patients to delay or abandon legitimate medical treatment, resulting in preventable suffering and death[53]. Zhang Xiangyu’s case specifically documented multiple patients becoming ill under her treatment, with some dying as a result of her fraudulent methods[54]. The substitution of supernatural healing for evidence-based medicine created a public health crisis that required government intervention.

Psychological harm manifested in what medical literature documented as “qigong-induced psychosis,” where intensive practice triggered mental health crises in vulnerable individuals. The phenomenon was particularly severe in China due to unsupervised practice and the integration of paranormal beliefs with traditional techniques[55]. The medicalization of qigong deviation as a psychiatric condition reflects the recognition that spiritual practices, when improperly conducted, can cause genuine psychological damage.

Financial fraud involved the systematic exploitation of practitioners through exorbitant fees for worthless training and treatments. Major organizations like Zhong Gong generated billions in revenue through hierarchical training systems that promised supernatural abilities in exchange for substantial payments[56]. The commercial exploitation of spiritual seeking created a predatory industry that enriched charismatic leaders while impoverishing their followers.

The scale of exploitation was enormous. With 60-200 million practitioners at the movement’s peak, even a small percentage of harmful outcomes represents hundreds of thousands of affected individuals[57]. The mass arrests following the 1999 crackdown, while politically motivated, also reflected the need to protect vulnerable populations from continued exploitation.

The lasting impact on Chinese society

The Qigong Fever’s suppression marked a decisive moment in contemporary Chinese history, establishing patterns of state control over spiritual expression that continue to shape Chinese society today. The movement’s rise and fall demonstrate the complex relationship between traditional culture, popular spirituality, and authoritarian governance in post-revolutionary China[58]. Its legacy includes both positive developments in healthcare integration and concerning restrictions on spiritual freedom.

The establishment of comprehensive regulatory frameworks represents one of the most significant long-term impacts. The Chinese Health Qigong Association’s control over public practice, mandatory state-approved training for instructors, and restrictions on group gatherings have created a system of spiritual surveillance that extends far beyond qigong[59]. This regulatory model has been applied to other traditional practices and religious movements, establishing the principle that spiritual expression must be mediated through state institutions.

The integration of validated traditional practices into mainstream healthcare represents a positive legacy. Qigong’s incorporation into Traditional Chinese Medicine curricula at universities since 1989 and its acceptance as complementary therapy in clinical settings demonstrate successful cultural preservation through scientific validation[60]. Modern research supporting qigong’s efficacy has enabled its global expansion as a wellness practice while maintaining connection to authentic Chinese traditions.

However, the stigmatization of traditional practices remains a significant concern. The association of qigong with fraud has damaged the credibility of traditional Chinese medicine more broadly[61], creating public skepticism that may prevent legitimate practices from receiving proper recognition. The loss of some authentic lineages and knowledge through suppression represents irreversible cultural damage.

Key Lessons from a Mass Phenomenon

The Qigong Fever represents one of the most complex and consequential cultural phenomena in modern Chinese history. Its rise from traditional practice to mass movement to political threat reveals fundamental tensions between cultural preservation, scientific validation, and social control in contemporary China[62]. The movement’s ultimate suppression established patterns of state management of spiritual expression that continue to shape Chinese society today.

The phenomenon emerged from the unique conditions of post-Cultural Revolution China, where ideological vacuum, cultural trauma, and the search for national identity created conditions for extraordinary popular mobilization around traditional practices. The initial government support reflected genuine belief that qigong could serve as a bridge between Chinese tradition and scientific modernity[63]. However, the movement’s evolution toward independent social organization and alternative authority structures ultimately made it incompatible with Communist Party control.

Zhang Xiangyu’s case epitomizes both the promise and peril of the Qigong Fever. Her ability to mobilize millions of followers demonstrated the profound spiritual hunger in Chinese society, while her fraudulent claims and the resulting harm revealed the dangers of unregulated charismatic authority. Her arrest and conviction marked the beginning of the end for mass qigong movements in China[64].

The academic analysis of this phenomenon provides valuable insights into the dynamics of cultural modernization, the relationship between tradition and science, and the challenges of preserving authentic cultural practices while preventing exploitation. The balanced scholarly approach that acknowledges both the fraudulent aspects and authentic traditions offers a model for understanding similar phenomena globally[65].

The lasting impact includes both positive developments in healthcare integration and concerning restrictions on spiritual freedom. While the regulatory framework has protected consumers from fraud and enabled scientific validation of legitimate practices, it has also created a system of spiritual surveillance that limits authentic cultural expression[66]. The challenge for contemporary China remains finding ways to preserve traditional knowledge while preventing exploitation, balancing cultural authenticity with scientific rigor, and maintaining social order while allowing spiritual expression.

The Qigong Fever ultimately serves as a cautionary tale about the need for balanced approaches to cultural phenomena that respect traditional knowledge while maintaining scientific rigor and protecting vulnerable populations from exploitation. Its legacy continues to influence debates about tradition, modernity, and cultural authenticity in China and beyond.

Palmer, David A. (2007). Qigong Fever: Body, Science, and Utopia in China. Columbia University Press. ↩︎

Baidu Baike. (2023). Zhang Xiangyu. https://baike.baidu.com/item/张香玉/5750960 ↩︎

China Underground. (2014). Rise and fall of the QiGong frenzy in China: when superstition and science collide. ↩︎

Samim.io. (2019). Paranormal and Qigong frenzy in China: Collection of texts & links. ↩︎

Baidu Baike. (2023). Zhang Xiangyu. https://baike.baidu.com/item/张香玉/5750960 ↩︎

Cult Education Institute. (2014). Rise and fall of the QiGong frenzy in China: when superstition and science collide. ↩︎

Baidu Baike. (2023). Zhang Xiangyu. https://baike.baidu.com/item/张香玉/5750960 ↩︎

China Underground. (2014). Rise and fall of the QiGong frenzy in China: when superstition and science collide. ↩︎

Palmer, David A. (2007). Qigong Fever: Body, Science, and Utopia in China. Columbia University Press. ↩︎

Wikipedia. (2024). History of qigong. History of qigong - Wikipedia ↩︎

Li, Yimeng. (2015). The Craziness for Extra-Sensory Perception: Qigong Fever and the Science-Pseudoscience Debate in China. Zygon: Journal of Religion and Science. ↩︎

Wikipedia. (2024). Qigong fever. Qigong fever - Wikipedia ↩︎

Wikipedia. (2024). Zhong Gong. Zhong Gong - Wikipedia ↩︎

Wikipedia. (2024). Falun Gong. Falun Gong - Wikipedia ↩︎

Human Rights Watch. (2002). Dangerous Meditation: China’s Campaign Against Falungong. Refworld. ↩︎

Pew Research Center. (2023). Government policy toward religion in the People’s Republic of China – a brief history. ↩︎

Wikipedia. (2024). Zhang Baosheng. Zhang Baosheng - Wikipedia ↩︎

DayDayNews. (2021). What happened to Zhang Baosheng, a smash hit in the 1980s? ↩︎

Retraction Watch. (2021). Journal retracts paper by ‘miracle doctor’ claiming life force kills cancer cells. ↩︎

Wikipedia. (2024). Zhang Hongbao. Zhang Hongbao - Wikipedia ↩︎

Dui Hua Human Rights Journal. (2014). Zhonggong: The Subversive Business of Qigong. ↩︎

Wikipedia. (2024). History of qigong. History of qigong - Wikipedia ↩︎

Li, Yimeng. (2015). The Craziness for Extra-Sensory Perception: Qigong Fever and the Science-Pseudoscience Debate in China. Zygon: Journal of Religion and Science. ↩︎

Wikipedia. (2024). Qian Xuesen. Qian Xuesen - Wikipedia ↩︎

Wikipedia. (2024). Zhang Zhenhuan (general). Zhang Zhenhuan (general) - Wikipedia ↩︎

China Underground. (2014). Rise and fall of the QiGong frenzy in China: when superstition and science collide. ↩︎

Wikipedia. (2024). Qigong fever. Qigong fever - Wikipedia ↩︎

Wikipedia. (2024). Persecution of Falun Gong. Persecution of Falun Gong - Wikipedia ↩︎

Pew Research Center. (2023). Government policy toward religion in the People’s Republic of China – a brief history. ↩︎

Palmer, David A. (2007). Qigong Fever: Body, Science, and Utopia in China. Columbia University Press. ↩︎

Palmer, David A. (2010). La Fièvre du Quigong: guérison, religion, et politique en Chine, 1949-1999. China Perspectives. ↩︎

Palmer, David A. (2007). Qigong Fever: Body, Science, and Utopia in China. Columbia University Press. ↩︎

Chen, Nancy N. (2003). Breathing Spaces: Qigong, Psychiatry, and Healing in China. Columbia University Press. ↩︎

Primidi. (2023). Qian Xuesen - Later Life. Technology Trends. ↩︎

Wikipedia. (2024). History of qigong. History of qigong - Wikipedia ↩︎

Li, Yimeng. (2015). The Craziness for Extra-Sensory Perception: Qigong Fever and the Science-Pseudoscience Debate in China. Zygon: Journal of Religion and Science. ↩︎

Wikipedia. (2024). Zhang Baosheng. Zhang Baosheng - Wikipedia ↩︎

Retraction Watch. (2021). Journal retracts paper by ‘miracle doctor’ claiming life force kills cancer cells. ↩︎

Palmer, David A. (2010). La Fièvre du Quigong: guérison, religion, et politique en Chine, 1949-1999. China Perspectives. ↩︎

VICE Fightland. (2017). When Qigong Masters Go Bad. ↩︎

Wikipedia. (2024). Wang Lin (qigong master). Wang Lin (qigong master) - Wikipedia ↩︎

South China Morning Post. (2013). Qigong master Wang Lin under scrutiny for ‘seven crimes’. ↩︎

Wikipedia. (2024). Xu Xiaodong. Xu Xiaodong - Wikipedia ↩︎

South China Morning Post. (2019). China’s censorship of Xu Xiaodong for exposing fake martial arts masters is alarming. ↩︎

Global Times. (2013). Qigong ‘masters’ struggle to survive. ↩︎

VICE. (2017). The MMA fighter on a mission to expose “fake martial artists” in China. ↩︎

Lu, Jianfei. (2004). Chinese Religious Innovation in the Qigong Movement: The Case of Zhonggong. ResearchGate. ↩︎

Palmer, David A. (2007). Qigong Fever: Body, Science, and Utopia in China. Columbia University Press. ↩︎

Chen, Nancy N. (2003). Breathing Spaces: Qigong, Psychiatry, and Healing in China. Columbia University Press. ↩︎

Wang, F. et al. (2020). Evidence Base of Clinical Studies on Qi Gong: A Bibliometric Analysis. ScienceDirect. ↩︎

National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. (2024). Qigong: What You Need To Know. NCCIH. ↩︎

China Underground. (2014). Rise and fall of the QiGong frenzy in China: when superstition and science collide. ↩︎

Natural Medicine Journal. (2009). An Evidence-based Review of Qi Gong by the Natural Standard Research Collaboration. ↩︎

Baidu Baike. (2023). Zhang Xiangyu. https://baike.baidu.com/item/张香玉/5750960 ↩︎

Medical News Today. (2023). Qigong: Benefits, types, side effects, and more. ↩︎

Wikipedia. (2024). Zhong Gong. Zhong Gong - Wikipedia ↩︎

Wikipedia. (2024). Qigong fever. Qigong fever - Wikipedia ↩︎

Palmer, David A. (2007). Qigong Fever: Body, Science, and Utopia in China. Columbia University Press. ↩︎

Wikipedia. (2024). History of qigong. History of qigong - Wikipedia ↩︎

Wikipedia. (2024). Qigong. Qigong - Wikipedia ↩︎

China Underground. (2014). Rise and fall of the QiGong frenzy in China: when superstition and science collide. ↩︎

Palmer, David A. (2010). La Fièvre du Quigong: guérison, religion, et politique en Chine, 1949-1999. China Perspectives. ↩︎

King, Dylan Levi. (2023). Cybernetics leftovers. Substack CJK. ↩︎

Baidu Baike. (2023). Zhang Xiangyu. https://baike.baidu.com/item/张香玉/5750960 ↩︎

Palmer, David A. (2007). Qigong Fever: Body, Science, and Utopia in China. Columbia University Press. ↩︎

Wikipedia. (2024). History of qigong. History of qigong - Wikipedia ↩︎