The Perfect Myth That Wasn’t

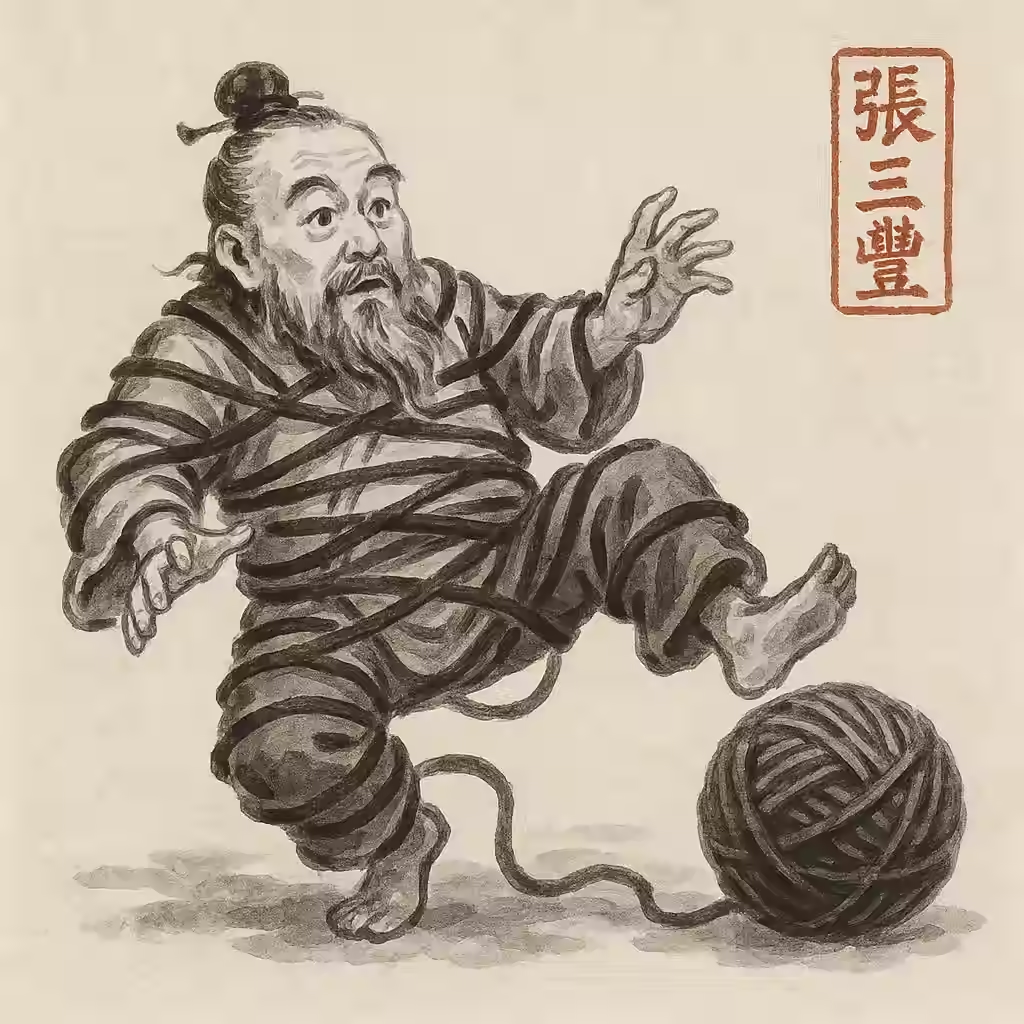

A seven-foot-tall Daoist immortal with a lifespan exceeding two centuries, who witnessed a battle between a snake and a bird before creating one of the world’s most revered martial arts systems. The tale of Zhang Sanfeng represents perhaps the most audacious and successful myth-making campaign in martial arts history—a fabrication so compelling that it continues to be marketed globally despite overwhelming evidence of its falsity[1].

Historical descriptions paint Zhang as a superhuman figure “with the bones of a crane and the posture of a pine tree, having whiskers shaped like a spear”—imagery designed to elevate him beyond mortal constraints and into the realm of the divine[2]. This mythologizing serves not merely as historical embellishment but as a calculated strategy with profound commercial, cultural, and political implications.

The Biographical Impossibility

The Zhang Sanfeng narrative collapses under even minimal historical scrutiny. The contradictions surrounding his basic biographical details are not merely inconsistencies but irreconcilable impossibilities. Historical records present wildly divergent accounts of when Zhang lived, variously placing him in the Song Dynasty (960-1279), the Yuan Dynasty (1279-1368), or extending his life well into the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644)[3].

Douglas Wile’s meticulous research reveals an even more problematic reality: “Zhang Sanfeng” appears to be a composite character cobbled together from multiple historical figures. One was a Six Dynasties period (220-589) Daoist master of sexual practices, another was a Song Dynasty “thrice crazy” wandering poet, and a third was the Yuan-Ming era Daoist most frequently associated with martial arts[4]. The lack of coherent identity suggests not historical ambiguity but rather intentional myth-making.

Even more damning is the timeline of Zhang’s supposed martial creation. The earliest documented reference linking him to martial arts only appears in the “Epitaph for Wang Zhengnan” written by Huang Zongxi in 1669—centuries after Zhang’s purported existence. This text merely credits him with developing an undefined “Daoist internal martial arts style” with no specific mention of Taiji[5].

The Chronological Impossibility

Modern historical research exposes a damning chronological problem: the term “Taijiquan” (Tai Chi Chuan) doesn’t appear in any reliably dated historical document until the shockingly recent 1912 “Taiji Fist Classics” published by archaeologist Guan Baiyi[6]. This places the first documented reference to Tai Chi nearly seven centuries after Zhang Sanfeng supposedly created it—an absurd historical gap that defies credibility.

Scholarly consensus now points to the Chen family of Henan Province as the actual originators of what became known as Tai Chi in the 17th century, placing its development centuries after Zhang Sanfeng’s alleged existence[7]. This evidence dismantles the cornerstone of the Wudang martial arts mythology, revealing it as a relatively modern invention retroactively attributed to a legendary figure to manufacture legitimacy.

The Political Manipulation

The tenacity of the Zhang Sanfeng myth reflects deeper cultural and political agendas rather than historical reality. During the politically tumultuous Republican era (1912-1949), the nascent Chinese martial arts community desperately sought legitimization. The Zhang Sanfeng narrative provided the perfect vehicle: an illustrious, quasi-divine lineage stretching back centuries before the better-documented Shaolin traditions[8].

This period coincided with surging Chinese nationalism and a desire to celebrate indigenous cultural achievements unsullied by foreign influence. The calculated promotion of a divinely-inspired martial art created by a Daoist immortal represented a uniquely Chinese contribution to world culture that could be positioned against foreign physical traditions[9].

The political dimensions became even more pronounced during the Cold War. Tang Hao’s groundbreaking research in the 1930s challenging the Zhang Sanfeng origin myth was systematically suppressed on mainland China until after the Communist revolution in 1949. Meanwhile, culturally conservative elements of the martial arts community who fled to Taiwan and Hong Kong aggressively promoted the Zhang Sanfeng theory, creating an ideological division that mirrored the political schism[10].

The Modern Manufacturing of Tradition

Despite overwhelming evidence debunking its mythical origins, Wudang martial arts experienced a calculated revival beginning in the late 20th century. After China’s reform policies under Deng Xiaoping in 1978, traditional practices once suppressed during the Cultural Revolution were strategically rehabilitated to serve economic and cultural objectives[11].

A pivotal moment came in 1980 when Jin Zitao, claiming to be a lineage holder of Wudang martial arts, demonstrated “Wudang Taiyi Wuxing Boxing” at a national martial arts event. This spectacle sparked renewed interest in Wudang traditions that had nearly vanished—or more accurately, had never existed in their claimed form[12].

The UNESCO declaration of the Wudang Mountains as a World Heritage Site in 1994 provided international legitimization and transformed the region into a lucrative tourism destination[13]. This recognition served as potent marketing for schools teaching “ancient” Wudang martial arts both in China and internationally, despite their questionable historical connections.

The Commercial Exploitation

Today, the Wudang Mountains draw over 70,000 international visitors annually, many specifically seeking martial arts instruction based on the fabricated Zhang Sanfeng lineage[14]. The city of Shiyan near Wudang boasts more than 25 martial arts schools capitalizing on this manufactured heritage[15]. These schools charge premium rates based on claims of teaching “authentic” traditions supposedly dating back to Zhang Sanfeng, despite these traditions being largely modern constructions.

The commercialization extends globally through martial arts schools claiming Wudang lineage, martial arts tourism, books, videos, and equipment—all marketed under the false pretense of connection to an ancient tradition. This represents a multi-million dollar industry built upon historical fiction presented as fact.

The Inconvenient Truth

The historical evidence presents an uncomfortable reality: Wudang martial arts as practiced today are largely modern constructions drawing on various Chinese martial traditions rather than ancient lineages. The term “Wudangquan” as a category for internal martial arts only gained prominence in the early 20th century when the newly formed Chinese Republic sought to categorize and systematize traditional fighting methods[16].

During the 1928 national martial arts tournaments organized by the Kuomintang government, participants were administratively divided into “Shaolin” and “Wudang” categories—with the latter encompassing tai chi, baguazhang, and xingyiquan. This bureaucratic classification helped cement the association between these arts and Wudang Mountain despite minimal historical evidence for such a connection[17].

In essence, what is marketed globally as an ancient tradition is predominantly a 20th-century creation retroactively linked to a legendary figure to manufacture historical legitimacy and commercial appeal. This systematic deception continues today, with thousands of practitioners unaware that their supposed connection to ancient wisdom is largely fictional.

Beyond Delusion: The Value of Honesty

Acknowledging the mythical nature of the Zhang Sanfeng narrative doesn’t necessarily diminish the value of Wudang martial arts. These practices offer valuable training methods focusing on internal development, health cultivation, and martial effectiveness. Their philosophical foundations emphasizing harmony with nature and internal energy cultivation remain relevant regardless of their actual historical origins[18].

However, there is profound value in honesty. The martial arts community has long operated in a realm where marketing hyperbole, invented lineages, and mythological origins are tolerated or even expected. This environment of accepted deception undermines legitimate scholarship and perpetuates cultural misunderstandings.

Rather than clinging to fabricated legends, practitioners would be better served by appreciating these arts for what they demonstrably are: evolving practices that reflect China’s complex cultural history, including its modern period of reinvention and cultural revival. The true power of Wudang martial arts may lie not in an imaginary lineage to an immortal creator but in their continued evolution and adaptation to contemporary needs while preserving core principles that have proven valuable through documented generations of practice.

In this light, whether Zhang Sanfeng ever existed becomes less important than recognizing the complex interplay of politics, nationalism, commerce, and genuine cultural preservation that continues to shape these traditions today.

Stanley Henning, “Ignorance, Legend and Taijiquan,” Journal of the Chen Style Taijiquan Research Association of Hawaii 2, no. 3 (1994): 1-7. ↩︎

“Zhang Sanfeng, a legendary culture hero,” China Daily, accessed April 15, 2025, https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/culture/art/2017-05/10/content_29066140.htm. ↩︎

Douglas Wile, Lost T’ai-chi Classics from the Late Ch’ing Dynasty (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1996), 23-28. ↩︎

“On the Historical Mystery of Zhang Sanfeng,” Okanagan Valley Wudang, accessed April 30, 2025, On the Historical Mystery of Zhang Sanfeng — Okanagan Valley Wudang. ↩︎

Huang Zongxi, “Epitaph for Wang Zhengnan” (1669), translated in Stanley Henning, “Ignorance, Legend and Taijiquan,” Journal of the Chen Style Taijiquan Research Association of Hawaii 2, no. 3 (1994): 4. ↩︎

Guan Baiyi, Taiji Fist Classics (Beijing: Beijing Physical Education Research Institute, 1912). ↩︎

Tang Hao, History of Chinese Wushu (Shanghai: Shanghai Cultural Press, 1935), 55-67. ↩︎

Charles Holcombe, “The Daoist Origins of Chinese Martial Arts,” Journal of Asian Martial Arts 2, no. 1 (1993): 10-25. ↩︎

Benjamin N. Judkins, “Zhang Sanfeng: Political Ideology, Myth Making and the Great Taijiquan Debate,” Kung Fu Tea (blog), April 4, 2014, Zhang Sanfeng: Political Ideology, Myth Making and the Great Taijiquan Debate – Kung Fu Tea. ↩︎

Douglas Wile, “Taijiquan & Daoism from Religion to Martial Art & Martial Art to Religion,” Journal of Asian Martial Arts 16, no. 4 (2007): 8-45. ↩︎

David Palmer, “The revival of Wudang Daoist martial arts,” Journal of Chinese Religions 45, no. 2 (2017): 124-147. ↩︎

“Wudangquan,” Wikipedia, accessed April 25, 2025, Wudangquan - Wikipedia. ↩︎

“Ancient Building Complex in the Wudang Mountains,” UNESCO World Heritage Convention, accessed April 20, 2025, https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/705/. ↩︎

“Wudang Mountain’s martial arts heritage draws global visitors,” Bastille Post, March 2, 2025, Wudang Mountain's martial arts heritage draws global visitors. ↩︎

“A Look at Wudang Wushu Revival,” Kung Fu Magazine, accessed April 28, 2025, http://www.kungfumagazine.com/magazine/article.php?article=1366. ↩︎

Meir Shahar, The Shaolin Monastery: History, Religion, and the Chinese Martial Arts (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2008), 187-193. ↩︎

Andrew D. Morris, Marrow of the Nation: A History of Sport and Physical Culture in Republican China (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004), 185-210. ↩︎

Adam D. Frank, Taijiquan and the Search for the Little Old Chinese Man: Understanding Identity Through Martial Arts (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006), 62-85. ↩︎